Self-Archiving Software in Institutional Repositories: Identifying Problems and Proposed Solutions

My last project update included information about self-depositing software in platforms such as Zenodo, Figshare, and the Open Science Framework (OSF). All the repositories and project management tools discussed have integrations with GitHub and other source code hosting platforms, which contribute to stable homes for software as well as encourage software citations. In addition to these platforms, institutional repositories (IRs) offer yet another location for self-depositing software. In my research into how Git repositories are archived, I am interested in whether or not institutional repositories are practical places for source code. My investigations, which are exploratory, consider the ways in which IRs handle more complex files—such as different types of source code and software—as well as how they account for multiple versions of a particular software. As part of this, I examine the limitations and problems that have been raised about IRs generally as well as various solutions suggested for moving beyond IRs in lieu of a more federated and networked system. One of the main questions in which I am interested is, what are the benefits and drawbacks of depending on the current distributed model of IRs for long-term preservation and access to source code?

What is an IR?

An institutional repository is a place to preserve and make accessible the scholarly and intellectual output of an institution. In general, IRs are maintained by academic libraries in higher education and offer the scholarly community an additional place to participate in open access (OA) through open access archiving, also known as self-archiving (Burns, 2013). According to the current listing in the Directory of Open Access Repositories (OpenDOAR) there are 3,689 institutional repositories worldwide and 449 IRs in the United States, the majority of which are maintained by universities. The early literature on institutional repositories provides insights into the motivations of their implementation and viewpoints vis-à-vis the rising cost of journal subscriptions and dwindling library budgets (also known as the ‘serials crisis’) and other critical issues related to scholarly communication. In Clifford Lynch’s 2003 essay “Institutional Repositories, Infrastructure for Scholarship”, he notes that the emergence of institutional repositories allows institutions to progress beyond their “historic relatively passive role of supporting established publishers” and that affordability, standards such as the Open Archives Metadata Harvesting Protocol for interoperability, and advances in digital preservation have made strides in transforming scholarship. Similarly, Chan (2004) notes that IRs have the potential to add value to the scholarly communication process and has created an avenue to make accessible pre- and post-prints as well as a variety of grey literature such as reports, technical findings, white papers, etc.

...a university-based institutional repository is a set of services that a university offers to the members of its community for the management and dissemination of digital materials created by the institution and its community members. It is most essentially an organizational commitment to the stewardship of these digital materials, including long-term preservation where appropriate, as well as organization and access or distribution.

—Clifford Lynch, Institutional Repositories: Essential Infrastructure for Scholarship in the Digital Age (2003)

Software in IRs

Source code and software are only occasionally listed in IR holdings, which are predominantly populated by more traditional research outputs such as journal articles (as pre- and post-prints), theses, dissertations, and grey literature. A cursory search for US-based IRs that contain software yielded only nine results from OpenDOAR. Of these nine repositories, seven were connected to a university, one of which is no longer maintained, and each ranged from having one piece of software to a few dozen. What is immediately apparent in searching these repositories for software is that each institution has a different interface and each varies in quality and overall usability. As a result, navigating each user interface (UI) took several minutes, if not longer, to locate software, and some had incorrect indexing (i.e. a dataset listed as software) and other discovery problems. As a specific example, many older (or seemingly older) repositories did not allow for faceted searching by item type, but rather only by subject or discipline. While some IRs were more difficult to navigate, there were several IRs that offered a better user experience. Specifically, Cornell University's eCommons (built on DSpace) and Columbia University’s Academic Commons (built on Fedora). These repositories both have attractive and useable interfaces as well as more robust options for discovering materials. Even with these features, however, problems still persist. While it is possible to find software in Cornell’s Commons, it requires multiple clicks to excavate down to where it is kept. Further, Columbia’s repository lists software by version but the various versions do not appear in sequence. For example, the entries for a Climate Predictability Tool (CPT) jump abruptly from version 15.7.11 to 16.11 and then has intervening entries for completely different software before resuming with a listing for other versions of the CPT software. In other words, instead of treating the software as a single entity with multiple versions (24 in total), each iteration is handled as a separate item, which results in potential confusion as they are not connected nor nested.

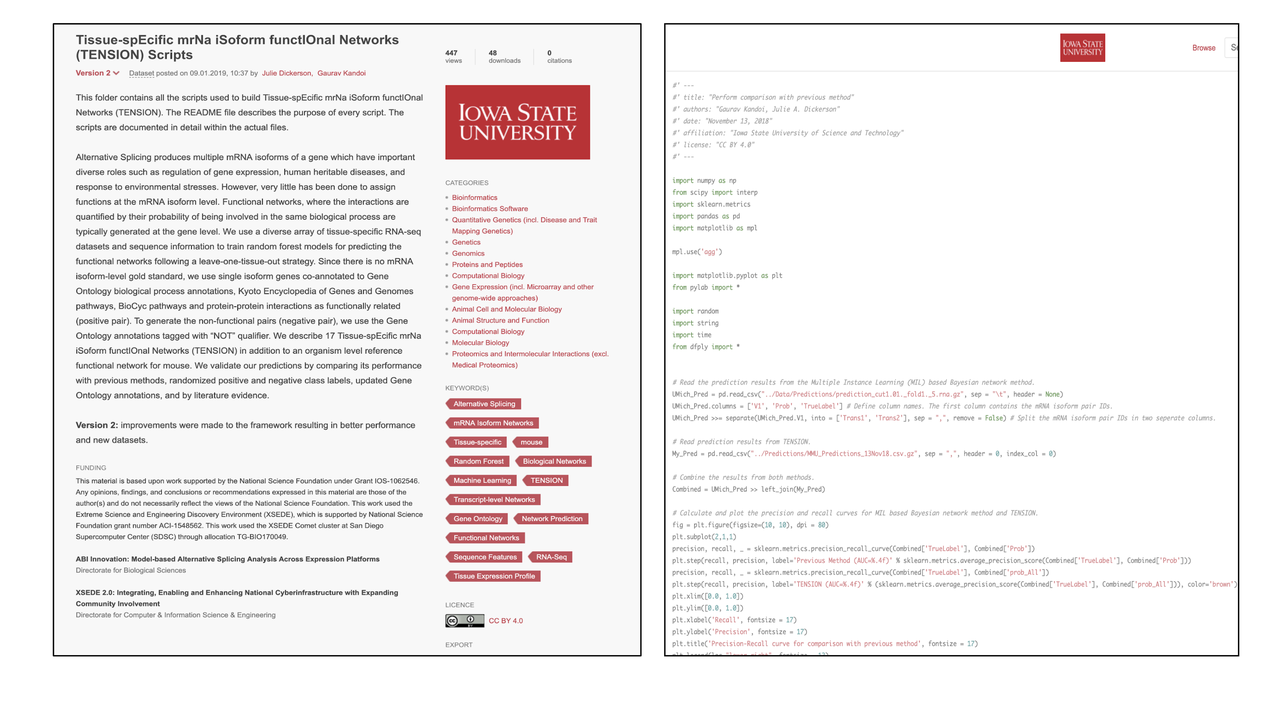

While OpenDOAR can be a (somewhat) helpful way of locating software in repositories, it was also necessary to see how data repositories made software discoverable to users. A search in Re3data.org, a registry of research data repositories, provided access to software held in data repositories, including those maintained by academic institutions. When compared to the IRs listed above, some major differences are readily apparent. For instance, there was much more software deposited in data and digital repositories, many of which were university repositories hosted on Figshare (i.e. https://iastate.figshare.com/, https://adelaide.figshare.com/, https://rdr.ucl.ac.uk/) as well as built in-house using Invenio (https://rodare.hzdr.de/). As discussed in my last post, depositing in places such as the OSF, Figshare, and Zenodo is certainly a popular option, especially given that these platforms have integrations with GitHub and provide DOI versioning. In contrast to the IRs encountered through OpenDOAR, the university data repositories built on Figshare provided a unified browsing experience with consistent iconography for each type of item (data set, software, etc.) across institutions. These sites require minimal excavation to get to the desired destination, and project elements (software, data, and related files) were bundled together, with DOI versioning included. Furthermore, code could be viewed within the platform itself, something very different than the download-only, compressed ZIP files provided by IRs.

Given that there are very few examples of software in IRs (and more software in “all-in-one” repositories hosted on 3rd party systems such as Figshare for Institutions as well the Open Science Framework for Institutions), one wonders about the future implications of these repositories and what it means for the future of IRs. To address and understand this, it will be helpful to review the literature on institutional repositories with an eye toward surveying the problems or shortcomings that have been raised by faculty and administrators alike. This exploration of IRs as a research topic is not meant as an indictment or critique of IRs or the IR concept. Rather, it is a means of identifying potential complications in regards to efforts to archive and preserve software and its ephemera and to become familiar with IR reform and new and emerging options and theories that look beyond the current distributed system.

Literature on IRs

While a full literature review is out of scope for a blog post, there are some interesting concepts related to IRs worth considering here, albeit briefly. In particular, the literature on IRs often center around certain terms and concepts such as “success” (Giesecke, 2011; Marsh, Wackerman, & Stubbs, 2017), “value” (Wacha & Wisner, 2011; Burns, Lana, & Budd, 2013), “faculty involvement” (Kim, 2011; Kyriaki-Manessi, Koulouris, Giannakopoulos & Zervos, 2013; Moore, 2011; Xia, 2008), “cost” (Burns, Lana, & Budd, 2013) and implementation and decision making (Bevan, 2008; Duranceau & Kriegsman, 2013; Lynch & Lippincott, 2005). Exploring these areas and what they mean for the longevity and viability of IRs provide lenses through which authors have approached and spoken about repositories at their institutions. As an example, faculty involvement and engagement have certainly been topics in IR literature for a long time and are presented as paramount to the success of an IR. Xia (2008), for instance, inquires about the correlation between disciplinary culture and the willingness of science scholars who deposit in a subject repository (SR) to do the same in an IR. While the study finds no correlation between the two, it does bring up some important issues such as faculty hesitation to deposit in both an SR and an IR. In addition, the study revealed that scholars were resistant to depositing materials if they perceived that doing so had little or no impact on them professionally. Xia also notes that faculty resistance might be driven by the fact that many IRs focus too much on policy and not enough on the presentation, feel, and quality of the repository itself (Xia, 2008). Further, a later study by Kim (2011) investigates factors that motivate or impede faculty participation and finds that digital preservation and copyright are important issues to the study’s survey participants. In particular, the study notes “universities' commitment to IRs depends on building trust with faculty and solving copyright concerns. Digital preservation and copyright management in IRs should be strengthened to increase faculty participation.” Of course, the themes or concepts mentioned above are not mutually exclusive. “Value” is often related to “cost” and “faculty involvement” is related to “success.” In turn, a nexus of ideas, standards, and policies of what makes an IR thrive is complicated, but seems to be intertwined with faculty and administrative buy-in, labor cost, decisions about software/hardware, dedicated library staff and administrators, and meeting the needs of researchers and faculty. As a result of these moving parts, it is understandable that some IRs thrive more than others and, likewise, that researchers, including librarians and library administrators, have raised some questions and voiced some critiques of IRs.

Problems Raised

While IRs have been presented as a positive contribution to open access and to the scholarly ecosystem, several authors have raised some critical concerns. An example of this is the brief, but bleak blog post by Eric van de Velde (2016) entitled “Let IR RIP.” In this post, van de Velde states that “The Institutional Repository (IR) is obsolete. Its flawed foundation cannot be repaired. The IR must be phased out and replaced with viable alternatives.” The reasons behind this stark determination are many. They include, for example, the lack of a “network effect” (in which the value of the service increases with the number of those using it). Further, van de Velde cites local management beholden to current faculty and administrators, restrictive (re)use rights, low use, high cost, and fragmented control (especially for scholars who work at a variety of institutions) as shortcomings of IRs. Finally, he notes a lack of social interaction, especially compared to subject repositories such as ArXiv, which is lauded as the “ideal federated IR,” as a weakness of the concept.

“The IR is not equivalent with Green Open Access. The IR is only one possible implementation of Green OA. With the IR at a dead end, Green OA must pivot towards alternatives that have viable paths forward: personal repositories, disciplinary repositories, social networks, and innovative combinations of all three.“

—Eric van de Velde, Let IR RIP (2016)

Others have adopted van de Velde’s position critiquing IRs. In an interview with Clifford Lynch titled “Open and Shut?: Q&A with CNI’s Clifford Lynch: Time to re-think the institutional repository?” (2016), Richard Poynder provides reasons that ostensibly contribute to the discordant discourse on the role of IRs and how it has caused ideological ”confusion [that] continues to plague the IR landscape.” While the introduction to the interview can be viewed as controversial (dissenting comments from the information community resulted in a follow-up post), there are some interesting points highlighted. In particular, the rise of platforms such as ResearchGate and Academia.edu, the success of Digital Commons, an increase in ArXiv-like disciplinary repositories, and the potential of the Open Science Framework to provide viable alternatives. In the interview portion, Lynch provides pragmatic answers to questions about the history and landscape of IRs. For example, in response to a question on the changing function and role of IRs, Lynch notes that US funding agencies seem to prefer centralized solutions rather than the IR model. This is an interesting response, especially in light of the recent announcement by the NIH promoting a pilot program with Figshare wherein all NIH funded researchers are encouraged to use the new NIH-Figshare repository. As with van de Velde, Lynch also addresses problems with the current distributed model IRs. He notes, “[t]echnology has moved on quite a bit in the last fifteen years, and it may be that it makes more sense to think about how to do this in a way that involves more shared or collective platforms and services rather than highly distributed approaches.”

“Technology has moved on quite a bit in the last fifteen years, and it may be that it makes more sense to think about how to do this in a way that involves more shared or collective platforms and services rather than highly distributed approaches.”

—Clifford Lynch, Introduction to Q&A with CNI’s Clifford Lynch: Time to re-think the institutional repository? (2016)

While these topics appear to be the product of current concerns and developments, it is not the first time strong critiques have been leveled at IRs. Dorothea Salo, in her article the Innkeeper at the Roach Motel (2008), has raised similar issues before—and with more robust explanations and first person accounts. Salo’s first-hand perspective of a digital repository librarian, a point of view that is often missing in a discourse dominated by cognitive and computer scientists and other non-librarians, allows her to connect the problems of IRs to the day-to-day business of maintaining them. Of particular interest are several key issues related to IR functionality and overall success, including but not limited to file versioning, access for faculty and support of research workflows, and the poor treatment of librarians and administrators dedicated to servicing, supporting, and managing an IR.

“Neither the open-access literature nor the library literature has gone much beyond threadbare platitudes and skill set laundry lists in discussing how best to fund, staff, and assess institutional repositories, further confusing the question of their viability.... Repository managers understandably focus on filling the repository at all costs, since the easiest (though undoubtedly the least useful) measure of repository success is growth in collections (even empty ones) and items (even useless ones).“

—Dorothea Salo,InnKeeper at the Roach Motel (2008)

A more recent critique of IRs comes from Arlitsch and Grant (2018) in their article ‘Why So Many Repositories?: Examining the Limitations and Possibilities of the Institutional Repositories Landscape.” In this study, the authors examine what they see as the “fragmented environment of institutional repositories” and raise issue with the duplication of cost and labor across institutions. They also discuss the problems inherent in managing multiple (and often out-dated) platforms and versions of IR software. The authors note, for example, that many IRs running on DuraSpace are out-of-date and are running version 1.8 or prior, causing not only challenges with the repository, but also security and ransomware risks (Arlitsch & Grant, 2018). Moreover, many institutions are running on versions prior to 5.X, all of which are unsupported as of January 2018 (6.X was the most current version at the time of the article). In addition, Arlitsch and Grant also note inconsistent metadata standards, poor service to users, and the ways in which libraries are unable to take advantage of collective data about content and users as shortcomings. The authors single out the “dispersed model” with “thousands of locally installed repositories” as problematic and note that it fails users (dually defined as users of the IR and those looking to self-archive) and ignores the advantages of the “networked effect.” They further cite problems with discovery in the distributed model, including struggles with harvesting and indexing in Google Scholar, which they see as “diminishing the value of aggregation.” The authors conclude that the problems inherent to IRs far outweigh the benefits. Further, they argue that the desire for local control of the “distributed model” does not serve users well and creates a “fragmented landscape that is not sustainable.” Although the authors acknowledge the contribution of IRs to open access and the efforts of libraries in accumulating the intellectual outputs of institutions, they nonetheless contend that this information be protected and migrated to a more collective and useful platform--one that “re-architect[s] to a large-scale, shared infrastructure that better serves our users.”

“...by continuing to manage thousands of locally-installed repositories, libraries and their users have failed to benefit from this network effect. “Many institutions describe a situation where they have as many as five different platforms (and perhaps as many as 20 or more actual independent instances of one of these multiple platforms) that have characteristics of IR.” (Coalition for Networked Information, 2017).“

—Kenning Arlitsch & Carl Grant, Why So Many Repositories? (2018)

IR Reform and Alternatives to the Distributed Model

While some critics think IRs need to be phased out, others see a way forward for them, albeit with reforms. Arlitsch and Grant, for example, suggest several remedies to the shortcomings highlighted in their article. These include combating the problems caused by “thousands of locally-installed repositories” by leveraging the “network effect.” The network effect is the idea or phenomena wherein value of a service increases when more people use it, and does so by taking advantage of cloud-based systems. Such a network effect can be seen in the wide-spread use of email/calendaring (Google, Microsoft, Yahoo!), Library Service Platforms, IR competitors, ResearchGate, and HathiTrust (Arlitsch, Grant, Colby, 2018). The article notes that the idea of a national-level repository is almost reflexively ruled out, but monolithic systems work well in other areas of researchers’ lives including sectors from commercial (GitHub) to IR-like (OSF) to cultural heritage (Europeana, HathiTrust) and disciplinary (ArXiv) (Arlitsch, Grant, Colby, 2018). Among the suggestions the authors put forward are using a more networked model, instituting 2.5% Commitment initiatives to support open scholarly commons infrastructures, and holding DuraSpace and OCLC more accountable for their roles in repositories. In particular, Arlitsch and Grant argue that DuraSpace and OCLC must be more responsive in overall efforts to find solutions for IR reform.

Discussions regarding ways to reform IRs and find alternate models have also extended to the role of research data management within an institution and how that relates to the IR. The notes from the 2017 Coalition for Networked Information (CNI) Executive Roundtable titled “Rethinking Institutional Repository Strategies” indicate that those in attendance saw this as a growing area of interest and inquiry. The participants indicated that many institutions are contending with the question of “how research data management relates to an IR, in particular different models about whether data sets being kept for the long term go into an IR or into some data specific repository and data preservation environment, perhaps run by the campus or perhaps externally operated.“ Roundtable members posited a close relationship between IRs and the need for careful data curation. The notes state, “In many instances, disciplinary data repositories will play an important role [in data preservation], but there is a long tail of datasets that will need institutional curation.” They then pose the question, “[a]re traditional IR platforms well equipped to handle them?” and answer with, “It varies based on the institutional needs and ambitions. If the institution handles fairly small, straightforward datasets such as Excel spreadsheets, they could probably put them in any platform. If the institution needs to manage and curate much larger datasets, they probably need something more specialized.”

The matter of data management in institutional IRs was only part of the discussion. Roundtable discussants also turned their attention to the fact that individual researchers are turning more often to platforms like Figshare. This well-known trend underscored the types of changes that CNI members see as being a necessary part of reforming and rethinking the IR model. They note, “one participant argued that libraries need to think of repositories as active hubs where social interaction for researchers could be built in.” They further state that this is already making its way into IRs, albeit slowly, through connections between library based systems and the OSF. Platforms such as Figshare and OSF are beginning to occupy this space by offering repositories tailored to the needs of academic institutions. A fairly recent addition called TIND, which is described as “a CERN spin-off providing solutions for library management and data preservation based on the CERN open source software Invenio,”offers a suite of options including a TIND IR and TIND RDM (which can be linked to GitHub) as solutions to various repository needs. TIND hosts Invenio on behalf of its clients and, according to the company’s blog, can “tailor the software to manage the whole pipeline of ILS needs including ingestion, classification, indexing, collection curation, dissemination and patron privileges.”

For many engaged in the dialogue regarding IRs, their reform, and their future, attention has also turned to “Next Generation Repositories.” The Coalition for Open Access Repositories (COAR) has taken up the challenge of developing a framework for next generation repositories. According to COAR, the main precepts behind this type of repository are: cross-repository interoperability by “leveraging web-friendly technologies and architectures,” developing services that support activities like “real-time curating, sharing, quality assessment, [and] content transfer,” and transforming scholarly communication by facilitating “open content, … real-time dissemination, and collective innovation.” In particular, these Next Generation repositories are envisioned as being a “distributed, globally networked infrastructure for scholarly communication, on top of which layers of value added services will be deployed, thereby transforming the system, making it more research-centric, open to and supportive of innovation, while also collectively managed by the scholarly community.” In theory, these repositories will encourage “the creation of cross-repository added-value services” and be able to support not only providing access to papers, but also to “datasets, pre-prints, working papers, images, [and] software...” Moreover, they will have uniform interfaces, making it easier for humans and machines alike to navigate and contribute to improved cross-repository searching, metadata/content harvesting, and the creation of intelligent tools.

While next generation repositories focus on distributed, global systems, some scholars theorize and imagine more fully decentralized models. In a plenary address at CNI’s Scholarly Communication: Deconstruct and Decentralize?, Herbert Van de Sompel, a member of the COAR Next Generation Working group, provides an example of decentralization in his discussion of a hypothetical system of researcher “pods.” In part, the pod concept is inspired by the work of Sarven Capadisli’s dokie.li and his autonomous linked research as well as Amy Guy’s work and ideas of a personal web observatory. In the model that Van de Sompel offers in his address, each researcher/academic maintains a personal, web-based research pod that allows them to post original content, comment on other scholars’ content, elicit peer review, perform reviews of other scholars’ works, and publish dynamically to the web. Van de Sompel argues that this approach would allow researchers to be in full control of their scholarly output while still providing much-needed mechanisms for registering work, certifying work, and providing provenance. In addition, he states that this system would be globally interoperable and would follow the researcher across her or his career regardless of changes in home department (or even, potentially, departure from academia). These ideas of global reach, distribution, and interoperability aligns closely with work that he and Martin Klein carried out at Los Alamos National Laboratory. The endeavor, titled the Scholarly Orphans project, calls for a networked, institutional centered approach. Its paired with a tool called Memento Tracer, which creates a WARC file of scholarly artifacts located across the web (including GitHub repositories). These captures are ingested into an institutional repository then sent to a cross-institutional web archive, which is the basis of a scholarly web archive. To date, they have completed a small scale test with 16 participants who are tracked using ORCID IDs and handles. The project employs algorithms to check platforms that academics tend to use (using the API of each site) to see if new content is available for each of the participants. If any new content has been added to the site, it is captured and is logged. Theoretically, this approach would allow institutions interested in capturing and preserving faculty work to establish an automated workflow designed to be updated as frequently as desired.

While these projects are limited to theorizing concepts, small case studies, and prototypes, they provide food for thought and open a portal to a worldview that is quite different than one focused on continuously rehabbing the current IR system. As seen with critiques of IRs and proposed solutions that view accountability, collaboration, and interoperability as ways to ameliorate problems raised, the futures of repositories is certainly unfolding, but it is likely that whatever solutions are operationalized—they will likely be more networked and more supportive of a cohesive scholarly output that includes papers, data, and, importantly, software.

WHAT'S NEXT?

In my next blog post, I will be exploring programmatic captures of source code. As noted previously, ISAGE is in active conversation about all topics in our blog posts. As I move through my environmental scan of the scholarly git landscape in general, and of software preservation in particular, and research various archival methods including, but not limited to, web archiving, self-archiving, software preservation, etc., I invite your insights, thoughts, and recommendations for further research. You can contact Vicky Steeves and me via email or submit an issue or merge request on GitLab.

Bibliography

Arlitsch, K., & Grant, C. (2018). Why So Many Repositories? Examining the Limitations and Possibilities of the Institutional Repositories Landscape. Journal of Library Administration, 58(3), 264–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2018.1436778

Arlitsch, K., Corbly, D., & Grant, C. (2018). Why So Many Repositories? Examining the limitations and possibilities of the digital repositories landscape [Presentation]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2485961

Awre, C., & Green, R. (2017). From Hydra to Samvera: An open source community journey. Insights: The UKSG Journal, 30(3), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.383

Ayers, P. (n.d.). LibGuides: Citing & publishing software: Publishing research software. Retrieved July 8, 2019, from https://libguides.mit.edu/c.php?g=551454&p=3786120

Bevan, S. J. (2007). Developing an institutional repository: Cranfield QUEprints – a case study. OCLC Systems & Services: International Digital Library Perspectives, 23(2), 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1108/10650750710748478

Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. (2017). Filling the repository—Harvard Open Access Project. Retrieved from https://cyber.harvard.edu/hoap/Filling_the_repository

Burns, C. S., Lana, A., & Budd, J. M. (2013). Institutional Repositories: Exploration of Costs and Value. D-Lib Magazine, 19(1/2). https://doi.org/10.1045/january2013-burns

Chan, L. (2004). Supporting and Enhancing Scholarship in the Digital Age: The Role of Open Access Institutional Repository. Canadian Journal of Communication, 29(3). https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2004v29n3a1455

Coalition for Networked Information. (2017). Rethinking institutional repositories: report of a CNI executive roundtable. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.cni.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/CNI-rethinking-irs-exec-rndtbl.report.S17.v1.pdf

COAR. (n.d.). COAR – Towards a global knowledge commons. Retrieved July 8, 2019, from https://www.coar-repositories.org/

Data Curation Network. (n.d.). Data Curation Network. Retrieved August 19, 2019, from https://datacurationnetwork.org/

DOAR. (n.d.). Directory of Open Access Repositories - v2.sherpa. Retrieved July 2, 2019, from http://v2.sherpa.ac.uk/opendoar/

Duranceau, E. F., & Kriegsman, S. (2013). Implementing Open Access Policies Using Institutional Repositories. In P. Bluh & C. Hepfer (Eds.), The institutional repository: Benefits and challenges (pp. 75–97). Chicago: American Library Association. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/alcts/sites/ala.org.alcts/files/content/resources/papers/ir_ch05_.pdf

Fruin, C. (2019). LibGuides: Scholarly Communication Toolkit: Repositories [LibGuide]. Retrieved June 13, 2019, from https://acrl.libguides.com/scholcomm/toolkit/repositories

Giesecke, J. (2011). Institutional Repositories: Keys to Success. Journal of Library Administration, 51(5–6), 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2011.589340

Hutchens, C. (2010). An Interview with Suzanne Bell, Administrator of the University of Rochester’s New Open Source Institutional Repository, UR Research. Serials Review, 36(1), 37–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.serrev.2009.11.006

Kim, J. (2011). Motivations of Faculty Self-archiving in Institutional Repositories. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 37(3), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2011.02.017

Kyriaki-Manessi, D., Koulouris, A., Giannakopoulos, G., & Zervos, S. (2013). Exploratory Research Regarding Faculty Attitudes towards the Institutional Repository and Self Archiving. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 73, 777–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.02.118

Lawley, E. (2019). Publication and Evaluation Challenges in Games & Interactive Media. Presentations and Other Scholarship. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.rit.edu/other/919

Li, Y., & Banach, M. (2011). Institutional Repositories and Digital Preservation: Assessing Current Practices at Research Libraries. D-Lib Magazine, 17(5/6). https://doi.org/10.1045/may2011-yuanli

Lynch, C. (2017). Updating the Agenda for Academic Libraries and Scholarly Communications. College & Research Libraries, 78(2), 126–130. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.2.126

Lynch, C. A. (2003). Institutional Repositories: Essential Infrastructure for Scholarship in the Digital Age (pp. 1–3). Retrieved from https://www.cni.org/wp-content/uploads/2003/02/arl-br-226-Lynch-IRs-2003.pdf

Lynch, C. A., & Lippincott, J. K. (2005). Institutional Repository Deployment in the United States as of Early 2005. D-Lib Magazine, 11(09). https://doi.org/10.1045/september2005-lynch

Marsh, C., Wackerman, D., & Stubbs, J. A. W. (2017). Creating an Institutional Repository: Elements for Success! The Serials Librarian, 72(1–4), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2017.1297587

Mangiafico, P. (2017). Rethinking Repositories: Time to (re-)focus on the researchers? https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4836293.v1

Moore, G. (2011). Survey of University of Toronto Faculty Awareness, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Scholarly Communication: A Preliminary Report. Retrieved from https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/26446

Novak, J., & Day, A. (2018). The IR Has Two Faces: Positioning Institutional Repositories for Success. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 24(2), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2018.1425887

Outten, C. (2019). Research Guides: Scholarly Communication: Institutional Repositories. Retrieved June 13, 2019, from //csulb.libguides.com/c.php?g=39245&p=250108

Poynder, R. (2016). Open and Shut?: Q&A with CNI’s Clifford Lynch: Time to re-think the institutional repository? Retrieved July 8, 2019, from Open and Shut? website: https://poynder.blogspot.com/2016/09/q-with-cnis-clifford-lynch-time-to-re_22.html

Rieh, S. Y., Markey, K., St. Jean, B., Yakel, E., & Kim, J. (2007). Census of Institutional Repositories in the U.S.: A Comparison Across Institutions at Different Stages of IR Development. D-Lib Magazine, 13(11/12). https://doi.org/10.1045/november2007-rieh

Saini, O. (2018). The Emergence of Institutional Repositories: A Conceptual Understanding of Key Issues through Review of Literature. Library Philosophy & Practice, 1–19.

Salo, D. (2008). Innkeeper at the Roach Motel. Library Trends, 57(2), 98–123. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.0.0031

Sutton, S. (n.d.). Accelerating academy-owned publishing. Retrieved from IO - In the Open website: http://intheopen.net/2017/11/accelerating-academy-owned-publishing/

The 2.5% Commitment.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/1805/14063/The%202.5%25%20Commitment.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Van de Sompel, H. (2017). Scholarly Communication: Deconstruct & Decentralize? Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o4nUe-6Ln-8

Van de Velde, E. (2016). Let IR RIP. Retrieved July 9, 2019, from SciTechSociety website: http://scitechsociety.blogspot.com/2016/07/let-ir-rip.html

Wacha, M., & Wisner, M. (2011). Measuring Value in Open Access Repositories. The Serials Librarian, 61(3–4), 377–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2011.580423

Xia, J. (2008). A Comparison of Subject and Institutional Repositories in Self-archiving Practices. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34(6), 489–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2008.09.016

Zeller, M. (2018). Research Guides: How to make your scholarly work open access: Self-archiving. Retrieved from https://libguides.wustl.edu/c.php?g=47489&p=304111